Following close upon the golden

jubilee celebrations of ‘victory’ in the 1965 war against Pakistan, with its

imbedded celebration of the Anglo-Indian hero Alfred Cooke, has come another

moment of remembrance in the history of the Indian state: the passing of

J.F.R. Jacob. Jacob was, more or less famously, the only ‘Jewish general’ in

the Indian Army and one of the architects of the Pakistani surrender in the

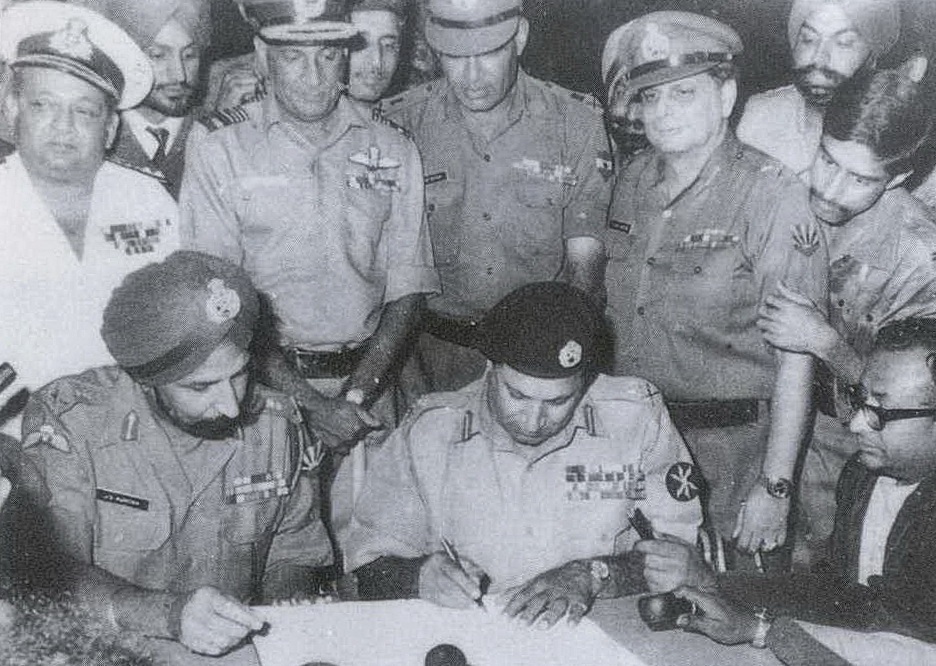

Bangladesh War. His visage graces the iconic photograph of the

surrender ceremony in Dhaka in 1971. (Jacob stands towards the right of the frame, above, with a young Air Force officer gripping his arm.) By his own admission, Jacob was not a religious man and may

not have been entirely comfortable with the tendency of his admirers – mainly

Indian and Israeli – to underline his Jewishness. Nevertheless, every obituary

has led with some version of ‘Jake the Jew.’

How extraordinary

this treatment is must be emphasized. When Sam Maneckshaw, the most celebrated soldier in Indian

history, died not long ago, few headline-writers in the mainstream press thought

to describe him as ‘the Parsi general,’ and no eulogist gloated about the fact

that a Zoroastrian had led the Indian Army. Likewise, when Air Chief Marshall Idris

Latif, the only Muslim to head an Indian military service, passes away, his

religion will be mentioned politely in the small print, as is only right. Denis La Fontaine will not be 'India's Christian air chief'; Christians are too prosaic. Clearly,

being a ‘minority,’ in and of itself, is not all that noteworthy. When it is

noteworthy, it is unevenly so: Alfred

Cooke was embraced in spite of his

Anglo-Indian ancestry (and even then, nobody mentioned his religion), but Jacob was celebrated because he was an Indian Jew. Coming at a time when minorities are

not especially popular in India, this invites us to think about the conditions

under which a national majority becomes generous towards the impurities it

contains.

The concept of a ‘minority’ is

something of a novelty. It became meaningful only in the nineteenth century, as

a corollary of the new institutions of popular sovereignty and the democratic

nation-state. In India, the term was most firmly associated with Muslims,

beginning with colonial historiography, proceeding through Aligarh’s

foundational debates and the nationalist polemics of the 1880s and 1890s, and

becoming concretized in the Minto-Morley reforms of 1909. Partition reinforced

the concrete, but also added a new complication by making policy (management) rather

than politics (accommodation) the normative idiom of relations between the

majority and the minorities. Throughout this trajectory, the concept secreted

layers of negative connotations: not only was it a calamity to be a minority,

it was a misfortune to have minorities.

In much of this, the Indian experience was consistent with trends in political

demography elsewhere in the world that emerged from the Great War.

Yet models exist in that world for

‘good minorities’ and even happy minorities. The best known such model is,

conveniently, known in America as the ‘model minority.’ That term has been used

since the 1970s to refer explicitly to ‘Asian immigrants,’ who do well at

school, do not trouble the police, and appear to affirm the ‘American’ values

of hard work, self-reliance (not relying upon government assistance), single-minded

acquisitiveness and ‘family,’ at a time (the aftermath of the Counterculture

and the Civil Rights Movement) when ‘Americans’ themselves had evidently wavered

in their faith in those things. The deconstruction of the model minority,

coming in the first instance from Asian American scholars like Ronald Takaki,

has been very thorough. Its critics have noted that while the notion

compensated somewhat for the virulence of the Asian Exclusion Acts, the lynch

mobs in the Pacific Northwest, the wartime internment of people of Japanese ancestry,

and seventy years of murder and dehumanization of ‘gooks’ and ‘slopes’ (who can

breathe easier now that attention has turned to ‘ragheads’ and ‘Art Malik’), it

has been more pernicious than generous. It has highlighted the success of some

Asians (mainly Japanese, Chinese, Koreans and Indians from middle-class backgrounds),

blacked out the less advantaged and successful, and trapped all Asian Americans within the exotic

category of ‘immigrant,’ to be contrasted with real Americans, whose realness

is reified by their imperiled virtues. The model minority is a handy stick

with which to beat other minorities (including Asians, but always and primarily

blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans) for their apparent fecklessness. Beyond

that, it has imposed on all minorities – the successful and the feckless – a

constricting model of citizenship that emphasizes docility: not challenging the

prerogatives of the majority, not questioning the meanings of success, not

taking over the ‘good schools’ and ‘excellent neighborhoods,’ not making waves.

The model minority is, in the final analysis, a model of apolitical citizenship

as the subjectivity of a ‘good’ minority, which allows the majority to bury its

history and politics of racism.

The notion of a ‘good minority’ is

not alien to India, where linguistic minorities have been a fact of political life

since the 1920s. In the Presidency capitals, an expanded political pie and massive

in-migration made it necessary for regional politicians to work out a language

that could accommodate – or isolate – the misfits. But who was a good minority

at the national level? For a long time, the answer was obvious: the model

minority in India were the Sikhs. Not only did they fit easily into the

anti-Muslim thrust of nationalist historiography, they were endowed with qualities

that Hindus were often unsure they possessed: Sikhs were industrious, ‘martial’

and hyper-patriotic. It was a nationalist redemption of the colonial trope of

the simple, loyal peasant-soldier. Sikhs themselves seemed to embrace their

role as semi-detached Hindus, and happily referred to themselves as the ‘sword

arm of the nation.’

The fragility of this model of

minority citizenship became inescapable in the 1980s, with the onset of Sikh

terrorism, the Delhi pogrom, and the years of profiling and ‘encounter’

killings. When Shabeg Singh, another icon of the 1971 war, used his military

expertise against the Indian Army in

Operation Blue Star, the hero became the traitor in shockingly literal terms.

The wounds healed with Manmohan Singh’s stint as prime minister, but not

completely. The romance was gone, and the good minority is nothing if not a

romantic concept: a specter of the majority’s love affair with its own national

mythology.

What went wrong with the Sikhs? It

was not simply the demands for autonomy or secession. It was the revelation of

a reluctance to accept the status of quasi-Hindus, which fully-credentialed

Hindus could neither understand nor forgive. (Nothing is as embarrassing as

interrupted self-love.) Just as pertinently, Sikhs asserting their separateness

– whether from Hindus or from India – were able to mobilize politically. Even a

two-percent minority can do that when two percent is more than fifteen million

people, concentrated geographically and already equipped with political

organizations and useful histories. The otherwise useful Sikhs, therefore,

failed that crucial test of a lovable minority: docility.

If we return to the photograph of the

Pakistani surrender in 1971, in which the romance of Indian cosmopolitanism is fully

on display, we see immediately that Sikhs are well represented, notably by

General Arora, the senior Indian commander in the eastern theater. They are

not, however, performing as a minority. Being politically alive and viable,

Sikhs are not exotic. They are not in the frame as curiosities. General Jacob

is. Some three decades ago, a relative of mine – a retired group captain in the

Indian Air Force – told me that Jacob’s presence at the ceremony was intended

to compound the Pakistani humiliation by forcing them to surrender to a Jew. It

is difficult to imagine Indira Gandhi and Jagjivan Ram plotting such a detail,

but it is significant that it was the perception of Indian officers with some

awareness of world politics. Jacob in 1971 was already a symbolic Jew.

He was also the most perfect kind of minority:

a man with a race but without a racial community. The number of Jews in India

is so small (barely five thousand) that mobilizing as a community – coming together

with an agenda and a means of applying pressure – would seem to be out of the

question. Indian Jews can, at most, express their dismay when some fool in

Ahmedabad opens a boutique called ‘Hitler.’ They are, in that sense, a docile

minority, and can be placed on the shelf of the nation's trophies. The same can be

said for Parsis. They too are a model minority, running gracefully out of

bodies and vultures. The Tatas have put to rest the old Parsi reputation of being ‘bum-lickers

of the English’: a stigma that Anglo-Indians could not fully escape. In Bapsi

Sidhwa’s novel Cracking India, a

Parsi woman in newly independent Pakistan explains to her child that they

are, and must remain, like sugar in a cup of tea: sweetening and invisible. But

the Parsi predicament is also different from that of Indian Jews. Jews are more

useful. Being Parsi has no global significance. Jewishess does, and that meaning

dovetails with specific Indian agendas, historical and contemporary.

The post-1945 Zionist tendency to

deploy an exceptional and existential victimhood – ‘everybody hates us, so

everything is justified’ – has made it possible for Indian nationalist

discourse to claim an exception of its own. In India, the narrative goes, Jews

were never persecuted. This may very well be true, give or take the Inquisition in Goa. But the assertion has not only allowed the spokesmen of the Indian

majority to proclaim their own ‘tolerance’ and inherent cosmopolitanism (which,

it turns out, is compatible with fascist imaginings of nationhood), it has also

aligned them with a strand within contemporary Zionism, which is its anti-Muslim

animus. This promises to take Hindutva politics out of the backwater, connecting it to another national narrative and a global concern (articulated in terms of ‘terror,’ ‘security' and 'Islam'). It also cements the

relationship between India and Israel at a time when both states have reached a

majoritarian nadir.

It may be, of course, that eulogists casually invoking 'Jake the Jew' are merely drawing attention to a harmless bit of trivia, without political 'intentions' or 'agendas.' When they do that, however, they reduce race and the racialized individual to trivia: the harmless fluff that is the essence of a model minority. The harmlessless is tied up with utility and the comfort of the majority; for that reason, it is political. The celebration of General Jacob’s

Jewishness then feeds (and feeds upon) majoritarian self-congratulation and tokenism, and simultaneously

sharpens the distinction between good and bad minorities in India. The more or

less solitary Jew, identified with national victory and

globally aligned with power and civilization, is good. The Muslim, with his

numbers and birthrate and place in history, is not. He is the trouble the Jew

does not give the nation. He is unser Unglück.

Sikhs have proved to be manageable; they can be either pogrom victims or prime

ministers.

Jacob was not an innocent observer in

the politics of his identity. He may have been ambivalent about his faith, but

he took racial identity seriously enough to work hard for closer ties between the Indian and Israeli states. That effort, while understandable,

highlights an important dynamic of being a model minority. It shows where, and

with whom, one chooses to stand, and how one is willing to be used. When a

minority lacks the demographic means of political self-assertion, there still

remains the option of self-assertion on behalf of other minorities, within the

larger community with which it identifies. Jacob liked to say he was ‘Indian

through and through.’ I would like to think that that means standing in

solidarity with those Indians who are excluded from ‘model’ status. Such solidarity,

however, might mean that when you die, you would not be a national icon, but

merely a troublemaker.

January 18, 2016